WHAT IF THE MONSTER WAS YOU?

6 min read

The burden of responsibility can be distressing. The debate about the moral significance of our choices has been going on since the dawn of civilisation. Socrates argued that evil exists because people ignore what is good, Protestants claimed that everything is already written, and Kierkeegard highlighted the sickening sense of inadequacy when confronted with the real possibility of harming and a freedom that may not fully satisfy us. Living is a complex experience: the solemn chimes of time echo mercilessly. Our experiences rush between the tracks of good and evil, only to disperse into smoky distances, in a perpetual arc between the spasmodic desire to assert one’s own will and the fear of the judgement of others that might mortify us.

Imagine waking up one morning and starting a new story. It would be nice to wake up in the comfort of your bed, open the window and be flooded with daylight. But sometimes circumstances plunge us into crazy situations. Let’s say that we wake up in a blanket of golden smiling flowers, in the body of a very quiet child who realises that, for what unknown reason, has ended up in a pit. We get up and walk down an aseptic corridor before reaching a space where we meet a cheerful little flower, who addresses us with sweet and reassuring words.

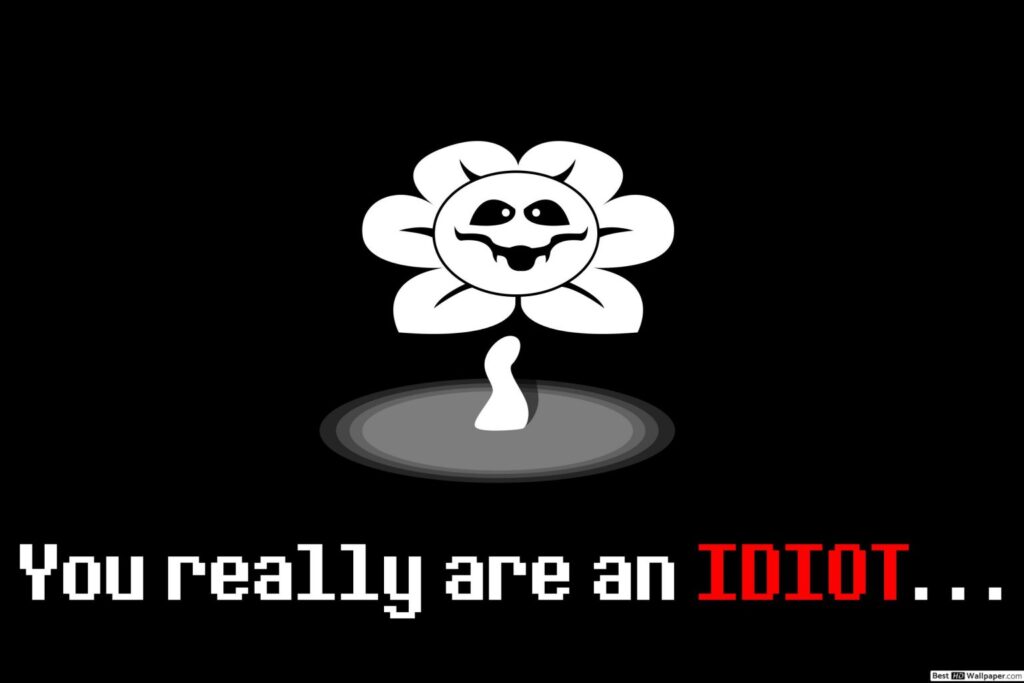

It says it is going to teach us how that world works, and at a certain point we are surrounded by little swirling bullets heading our way. They are the flower’s declaration of love, which, with its friendly naivety, invites us to accept it. As soon as we touch the bullets, that display of gratuitous goodness will turn into a weapon that will almost kill us, and the flower’s true intentions will emerge from the shadows. “In this world it is kill or be killed”: this is the law of the game, an icy gash that opens a perspective on the true nature of things. Life has always been a struggle for survival and what could be an opportunity for you, for another it could be a death sentence.

Undertale, a PC video game created by Toby Fox in 2015, begins this way. In a world with limited resources, the struggle for survival takes on dramatic turns and each man becomes a wolf for the other man, as Plautus said. The scenario of the game expands in front of us, showing us a universe populated by monsters, each of which is characterised by certain peculiarities but has its own story, life and emotional ties, just like those that each of us builds in our own existence. In the course of our virtual adventures we take it for granted that, in order to proceed in the plot, it is necessary to kill all the monsters, as if it were an obstacle race, precisely because we are the human beings and they are the monsters, and because after all it is only a video game: what could happen?

What can happen in reality is more than relevant, since no one can guarantee that our life is not just a simulation initiated by someone or something enjoying our adventures from an intergalactic screen, and maybe having a little fun when we get hurt. This is an initial consideration which cinema and science fiction have extensively developed. For example, Philip Dick contemplated a world in which human beings have been replaced by robots (and are unaware of it), and this would open up a thoughtful glimpse into the nature of free will, which we could address in another article.

Actually, if we decide to behave like pacifists, some things will happen, but if we are inveterate warmongers, other things will happen and new perspectives will open up in the course of the game, shedding light on the fabric of the plot, on the backgrounds of the characters and on what made them behave in a certain way. Just like in ‘real’ life. Because every attitude, even hostility, has its reasons in broad scenarios that are looking for answers; only in the darkest abyss of stupidity does a devouring void reign. The conclusion is that not everything is as simple as it appears.

In a complex and frighteningly fluid reality, all it takes is a slight push to slip from white to black and make oneself the author of the worst atrocities. But the truth is that in life there is no black and white, there is an infinite scale of greys modulated by an interweaving of rationality and emotions, fears and hidden desires that have to find a balance if we want to have a place in civilisation. As Freud himself argued, the price of civilisation is the rejection of our drives, which may re-emerge in the future in a more treacherous and elaborate form. It would be too simplistic to identify an eternal good and an absolute evil in order to relieve ourselves of responsibility and feel entitled to judge others because we think we are better than them.

The trap of morality lies in the fact that the righteous acquire an inalienable superiority over the criminal, the immoral pay for their sins by sinking into the depths of the Earth, and those who witness this without having full knowledge of what is happening often convince themselves that the punishment is completely deserved. Human beings have laid down the law on the concept of justice, stigmatising one side as the container of all possible evil (the underworld) and proclaiming the other as the source of abundant and saving good (the world of humans).

Those who are born under the light of a reality sustained by titanic contrasts often end up being swallowed up by one of the two sides and totally lose contact with the complexity of real life. The word ‘monster’ evokes something evil and is therefore fought regardless, without thinking too much about it; yet its etymology, from the Latin ‘mostrum’, simply indicates something prodigious and out of the ordinary, which can be frightening because of its diversity. But that does not make it right to condemn it a priori.

Flowey, the flower we met as the first character in the game, is desperate to destroy a world he calls sick, and to clean it up he decides to use the most barbaric violence. As punishment for the immorality of a universe that has caused so much pain to living beings, he decides to make innocent lives pay for the agony he himself has had to endure, strenuously convinced that once he has cleansed the world of its rottenness he will be able to build a better reality. But often the process of rising above the masses is paved with thorns that scarify every trace of innocence.

Thus, the concept of “purification” in most cases involves a pars destruens that precedes the pars costruens. The sick dream of the supremacy of the Aryan race, for example, would have had its roots in the extermination of all inferior populations. A biblical tribulation to prepare the ground for palingenesis, like the baptism of blood in the waters of the Red Sea necessary to forge the path of God’s people.

Men, however, are not hard and inflexible pieces of iron, as many legends tell us. On the contrary, they are constantly exposed to their own pain, to the pain of others and to the overflowing greed that instils in them the most absurd delusions of almightiness, which only highlight their inability to live a peaceful and quiet life, as so many people out there manage to do. And those who fly too high often come to a bad end, as we know. At the end of your journey, will you really be able to guarantee peace, or will you, like Napoleon, end up becoming what you yourself fought against with so much despair?

Source text: “E se il mostro fossi tu?” by Daniele Nicotera

Mi chiamo Giorgia Padovani e sono appassionata di lingue straniere da sempre. Nel corso degli anni ho studiato diverse lingue, arrivando a conseguire una laurea magistrale in interpretariato e traduzione con inglese e russo. Sono curiosa di natura e penso che ogni occasione sia buona per imparare qualcosa di nuovo. Ho vissuto le esperienze migliori della mia vita all’estero, prima in Cile e poi a Londra. Credo fortemente che il mondo sia troppo grande e vario per rimanere sempre e solo in un posto. Per questo mi definisco radicata, ma con lo sguardo rivolto al mondo. Tra le mie passioni, oltre ai viaggi, ci sono la lettura, la fotografia, il cinema e i musical