Bioart, a question of (aesth)ethics

7 min read

Bioart, Biotech Art, Genetic Art or Transgenic Art are different ways of defining an art form that makes use of biological material, genes processed in laboratories and transgenic organisms: a way of making art that has life itself as its protagonist and expressive tool.

‘The aim of Biotech Art is to lift the veil on what goes on inside genetics laboratories in order to question the technologies and learn how to use them’ – Jens Hauser, curator of the exhibition L’Art Biotech (Le Lieu Unique, Nantes, France, 2003).

Art is a vehicle for messages, ideas and ideologies that the artist wants to express and convey to anyone who stops to pay attention. Bioart wants to communicate technical-scientific progress, biotechnology in particular, pushing its limits to the extreme in order to create both curiosity and dismay in the public, which is forced to question itself about the possibility of “playing with” and upsetting biology as we know it, in the way nature intended.

Thus, on the one hand we have art, a discipline universally recognised as an expression of creativity, flair, fantasy, the transformation of abstract thought into visible, in some cases tangible, reality; on the other, we have science, which in the collective imagination is cold, rigid, the result of logic and rational schematisation. Nothing could be further from the truth: it is enough to live in the world of research, even if only for a short time, to realise that scientific thought is only the track which, through errors and attempts, moves scientists towards their goal, that most of the time passion, hypotheses, intuitions and serendipity are born in front of a sunset, reading a good book or having a chat with a friend, and not in front of a laboratory counter.

The combination of art and biology no longer appears as unrealistic and antithetical as it might have seemed at first glance. On the contrary, slipping from one discipline to the other is a filter through which it is possible to observe the great upheavals in the biotechnological field, whose rapid succession affects our existence very closely. Now it seems natural to talk about sensitive topics because of the use of new and unusual materials that are the result of technological progress, but as Joe Davis points out, these themes are also the oldest on Earth: DNA and microorganisms.

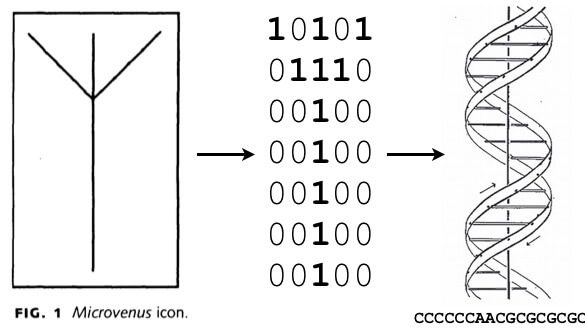

Joe Davis is a bio-artist who was the first to exploit the expressive potential of DNA, centring his artistic production on the symbolic value of the genetic code. His most famous work is Microvenus (1986), which was created in collaboration with Dana Boyd, a geneticist. The work was created to challenge the extreme stylisation of the female body depicted on the famous plates on the Pioneer 10 and 11 probes, created with the intention of being read by extraterrestrial life forms.

Using a culture of E. Coli bacteria, a Germanic rune, linked to the female goddess of earth and life, was encoded in a binary language.

Image source:www.clotmag.com/biomedia/joe-davis

With Microvenus, for the first time, a Petri dish, molecular biology techniques and a bit of artificial DNA become a canvas, brush and paint: “DNA has become an artistic medium” (Jens Hauser).

According to Eduardo Kac, a Brazilian writer and creator of the neologism “Bioart”, the bioartist, unlike the traditional artist, does not just create an art object but, through the manipulation of organic matter, makes living beings of varying complexity into art forms themselves.

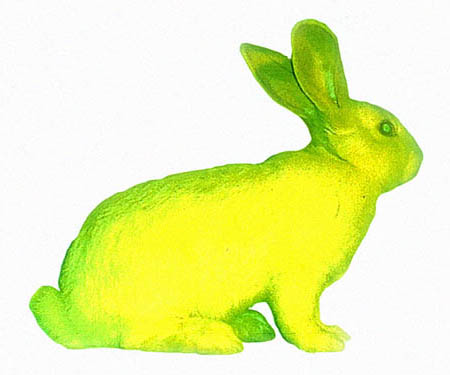

It is no coincidence that his most famous work is Alba, a fluorescent bunny.

Image source:www.genomenewsnetwork.org

Alba is part of the 2000 ‘GFP Bunny’ project , a name that is self-explanatory given that the animal’s fluorescence was obtained from the GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein), obtained from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria, using common and routine laboratory techniques. The ‘acquired’ fluorescence of the animal is visible through the use of blue light or special yellow filters.

However, the work has been the source of obvious objections: what are the rights of transgenic animals? Were they respected in the making of the work? Is it right to make a work of art out of a living being without its explicit consent? Moreover, it should not be forgotten that the debate on the creation of transgenic animals and the limits of human intervention in nature is already a sensitive issue in the biomedical field, which becomes particularly heated when interpreted for artistic purposes.

Kac’s intention, as he himself declared, did not stop with the creation of the fluorescent animal: the debate was not to focus exclusively on genetic manipulation, but the second phase of the work involved Davis himself adopting Alba, thus highlighting the problem of the social life of laboratory animals, destined to live in captivity in the enclosure and clearly to be the object of experimentation.

The step from (bio)artist to (bio)activist was really short at this point.

In 1991, the French artists Marion Laval-Jeantet, an artist and anthropologist, and Benoît Mangin, an artist, created the artistic duo “Art Orienté object” (AOo), to denounce the use of animals and plants in medical and cosmetic research and to raise awareness about genetic experimentation, in particular the use of tissue engineering. The two bio-artists have become famous for manipulating themselves to express their messages.

For example, they created the Skin Culture series in 1996, in which the artworks are tattooed epidermal tissues obtained from their own engineered epidermal cells with Cavia porcellus. With the Skin Culture project they wanted to question the boundaries between different species, especially since the fate of the tissue-works of art was to be grafted onto the bodies of collectors eager to buy and show them off.

Image source: https://artscy.sites.ucsc.edu/2014/11/25/marion-laval-jeantet-and-benoit-mangin/

With their works, AOo manage to pursue a form of bio-art that is strongly influenced by bio-activism. They are ironic, irreverent and shocking in many cases. For example, in 2011 they performed their best-known performance “Que le cheval vive en moi” (May the horse live in me), in which Marion Laval-Jeantet had horse blood injected into her body after several months of being given equine immunoglobulins under medical supervision to prepare her organism. This protocol was based on the principle of mithridatism, a term derived from King Mithridates, who had himself regularly injected with small quantities of a certain poison in order to become immune to it.

The performance ended with the “hybrid” blood being taken from the artist and frozen. For the duration of the performance, the artist wore special footwear, designed by herself, which ended in clogs and which recalled the shapes of the animal’s limbs. This allowed her to come into contact with the animal, to enter its Umwelt, its environment, and to establish communication, which was the ultimate aim of the performance.

The way different artists make Bioart should shake the audience and expose common anxieties, buried fears and bewilderment for what seems to be a chess game with God. Can man defeat decay and disease by dismantling and reconstructing the genome, in which everything we are is fundamentally written? Above all, is it right for man to intervene in what is the natural course of his existence: to be born, to develop and to die?

In this way, the audience inevitably comes up against the anguish over GMO crops, the pity over animals kept locked in cages, the misunderstanding over the formulation of vaccines and what they contain.

I leave the judgement on aesthetics to you: you may or may not like these works, you may or may not even consider them weird. The crude reality is that we should never stop at the most superficial level of reading art, but take a step further, scratch the surface of our prejudices and try to understand why that work arouses precisely those emotions, even if they are of disgust. It is only fair to reiterate that its purpose should be to make us ask “why” and push us to look inside ourselves to understand the world of the artist and his message, thus helping us to understand a new fragment of reality.

Read more:

Cover image by Pinterest

Source text: https://www.antropia.it/bioarte-una-questione-di-estetica/

Mi chiamo Giorgia Padovani e sono appassionata di lingue straniere da sempre. Nel corso degli anni ho studiato diverse lingue, arrivando a conseguire una laurea magistrale in interpretariato e traduzione con inglese e russo. Sono curiosa di natura e penso che ogni occasione sia buona per imparare qualcosa di nuovo. Ho vissuto le esperienze migliori della mia vita all’estero, prima in Cile e poi a Londra. Credo fortemente che il mondo sia troppo grande e vario per rimanere sempre e solo in un posto. Per questo mi definisco radicata, ma con lo sguardo rivolto al mondo. Tra le mie passioni, oltre ai viaggi, ci sono la lettura, la fotografia, il cinema e i musical