MASS TOURISM: ORIGINS AND CONTRADICTIONS

6 min read

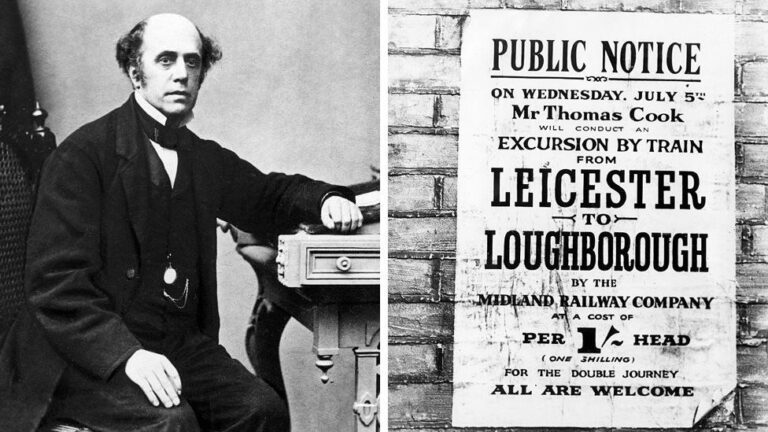

What would modern travel be without tourism? Is it possible, in the twenty-first century, to imagine a trip without our mind automatically linking it to tour guides, all-inclusive packages, endless lines at museum ticket offices or famous hotel chains? The idea of mass tourism, along with its set of advantages and contradictions, is now the equivalent of the trip itself to the point that the two concepts now seem inseparable. And yet, several years ago, traveler and tourist represented two totally different approaches to the discovery of the world. The two concepts started combining in the mid-nineteenth century thanks to the British businessman, now defined as the father of modern tourism: Thomas Cook.

Thomas Cook

Thomas Cook organized the first railway tour in history, but before becoming a tour operator he was a Protestant pastor who was dedicated to the social development of England of that time. Among the various campaigns he handled, there was the fight against alcoholism, a widespread problem especially among the poorest categories of the country. After realizing that just prayers were not convincing enough to dissuade from drinking alcohol, he decided to try a more concrete method. Hence the idea of organizing trips that would help people to distract themselves from alcohol addiction, and what better vehicle than the train which exactly at that time was spreading throughout the United Kingdom?

And so it was that on July 5, 1841, a train loaded with 600 people left for a twelve-mile journey from Leicester to Loughborough; a trip organized from start to finish, as Cook took care of everything: tickets, hospitality, meals, entertainment with religious hymns and even advertising the event on printed fliers, that is what we would now define an all-inclusive package.

So, Thomas Cook decided to start his own agency specialized in organized trips, the first travel agency in the world. At first, he organized trips within England, then toward Scotland, Ireland and, in 1855, the tour that made him famous beyond the British borders: from London to France with the final destination of the Universal Exposition in Paris.

From that moment on, Cook became unstoppable. His business spread like never before and his name started circulating all over the world, such that more than a century later the company’s slogan stated, with an untranslatable wordplay in Italian: “Don’t just book it – Thomas Cook it!”.

Those who relied on Cook packages could enjoy convenient discounts and reductions, considering the agreements between the agency and several hotels and restaurants all over the world. Cook was also the pioneer of the ‘circular notes‘, a sort of universal voucher that allowed tourists to travel abroad without having to change currency (thus anticipating the traveler’s cheque created in 1891 by American Express, which was Cook’s main rival in North America).

The pre-Cook journey

Even though, by then, Cook provided his services around the world, from North Africa to America, his method was not exempt from criticisms, especially from compatriots. Some members of English high society, such as the famous Victorian art critic John Ruskin, said that organized trips deprived travelers of that age-old enterprising and adventurous spirit that has always characterized human beings beyond the borders of their home. But the cornerstone of the criticisms against Cook was the awareness of the democratization of traveling, considering that, by then, there was a wide range of possibilities of traveling even for the middle-class and no longer, as it was before, only for a small élite of nobles and aristocrats.

So, modern tourism develops hand in hand with the growth of the middle-class. However, before this revolution in the ways and target of trips, moving from place to place was a privilege that only few people could enjoy. Before mass tourism, the trip was a pilgrimage of religious people or a way to increase their culture.

One of the most striking examples is the Grand Tour, a custom in vogue among young aristocrats of the XVII century (especially the British and Germans) which provided for a period of stay in the places of classical culture, firstly Italy. Abroad, the young nobles had the opportunity to study art and literature, visit ancient ruins and famous monuments or chat with the main intellectuals in Europe, in order to go back home with a wealth of cultural knowledge up to their future positions in politics or intelligentsia of their respective countries. In short, it was a sophisticated and highly cultural tourism.

So, it is not surprising that the opening of the tourist market to the middle-class was exposed to several criticisms. The aim of traveling went from high culture to simple entertainment and how much Thomas Cook’s project was praiseworthy, it cannot be denied that in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries the situation has definitely gotten out of hand. The wider travel accessibility, both in costs and in transports, made the whole experience more comfortable than in the past.

But comfort often has a price. When the means of transportation became faster and more risk-free and the hotels more luxurious and comfortable, the traveler’s search for adventure turned into a simple tourist’s search for pleasure. Whereas before the traveler was an active subject, always looking for new people and experiences, now the tourist is passive instead: he already knows what he will find inside the travel package and so he settles on a comfortable superficiality.

Boorstin and modernity

This is what the American sociologist Daniel J. Boorstin stated in his illuminating and prophetic essay of 1962, named From Traveler to Tourist: The Lost Art of Travel, moving up, by a few decades, the controversial consequences of mass tourism on the environment and local populations, mostly due to the influence of media and social networks on travel dynamics.

Boorstin analyzes the impact of tourism progress on modern man through a sarcastic eye on the reality of that time, highlighting how organized trips have reached a similar level of obsessive planning such that the tourist ends up not having the faintest interaction with local people.

Boorstin himself defines this phenomenon as the Environmental bubble, an expression that has its literal meaning and stands for that particular and by now usual circumstance where a tourist chooses a travel package full of services so familiar that he feels protected, safe, comfortable. These services are organized so that the tourist is enclosed in a comfort bubble, where the connection with the outdoor environment and local people is almost totally eliminated.

The most obvious examples are cruise ships, resorts, holiday villages and all those places designed for raising both physical and mentals barriers between the visitor and the visited place. Boorstin is ironic about the fact that, if it were not for a different view outside the windows, the modern tourist would not even have the impression of having left, of being in a different place from home. After all, “beds, lighting, air conditioning, central heating, pipes are all American-style although the shrewd hotel management will try to preserve a certain ‘local vibe’” as Boorstin writes about the recurring homologation of the hotel chains outside of America.

As we said before, tourism is the equivalent of the trip itself. But, despite the fact that physical movement has become much faster and safer than in the past during the last decades, our mind seems unable to adapt at the same speed to similar changes in space and motion and tends to seek comforting certainties rather than letting go of the adventure of a trip abroad. Progress in technique is unstoppable, there is no doubt, but the awareness of being able to move from side to side of the planet in a matter of hours of flight can still be so destabilizing that the human mind could continue to feel to the point of departure, even though the body is already miles away from home. So, paradoxically, an impromptu trip near home, maybe on foot or by bike, may seem more real, authentic and meaningful to us than a flight to another continent.

Bibliography:

https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/thomas-cook-history-timeline/index.html

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Cook

Boorstin Daniel J., “From Traveler to Tourist: The Lost Art of Travel”. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America (1962)

Cohen Erik, Toward a Sociology of International Tourism (1972)

Mi chiamo Giulia. Diplomata al liceo classico, ho in seguito conseguito la laurea triennale in Interpretariato e Comunicazione e poi la laurea magistrale in Traduzione Specialistica. Ho lavorato sia come traduttrice per una piattaforma digitale sia come interprete di conferenza in sede di udienza. Ho da sempre avuto una forte propensione per le lingue straniere motivo per cui ho deciso di intraprendere questo percorso. Sono anche appassionata di cucina, cinema ma soprattutto di film e serie tv